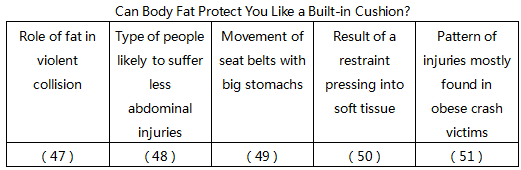

Fat can indeed act as a shock absorber in violent collision. A 2003 study of car-crash victims found that those with more fat were less likely to suffer abdominal injuries. But the fat-as-airbag principle only goes so far. When a driver is flung forward, the heavier his or her body, the greater the force required to stop it.

The pelvis is the primary load-bearing structure for scat-belt safety, Kent, an American scientist, says. But with big stomachs, seat belts slide up and off the lap. Since a restraint works best once it engages with a dead body, any time it spends pressing into soft tissue will delay that protective effect.

To observe this, Kent defrosted eight dead bodies and belted them into car seats for a 30mph crash. High-speed video showed that the obese bodies flew off their seats pelvis-and lower-chest first. Smaller subjects’ hips stayed in place as their heads and the main body thrown against the upper strap. That may help explain the pattern of injuries typically seen in obese crash victims—more damage to the legs, less to the head, and a greater likelihood of death.